We finally published our special issue on Policy Innovation in the Global South and South-North Policy Learning with the Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis @JCPA_ICPA. Some of the contributions are free of access for the next couple of weeks so check them out. If you cannot find them, send me a message to @achkem for ungated versions.

The special issue covers an important topic, a topic which is also dear to me personally: Giving credit where credit is due to the enormous potential policy innovations in the Global South hold for the Global North. Standard literatures in public policy and related fields such as economics or social sciences tend to overlook or underestimate the learning potential stemming from policy innovations in the Global South. Even if they concede the potential of policy innovations in the Global South they rather think of this a sources of lateral learning (e.g. among countries of the Global South). The World Bank is a good example for such a segmented approach of learning which deems innovations from the Global South being mainly relevant for other countries of the Global South.

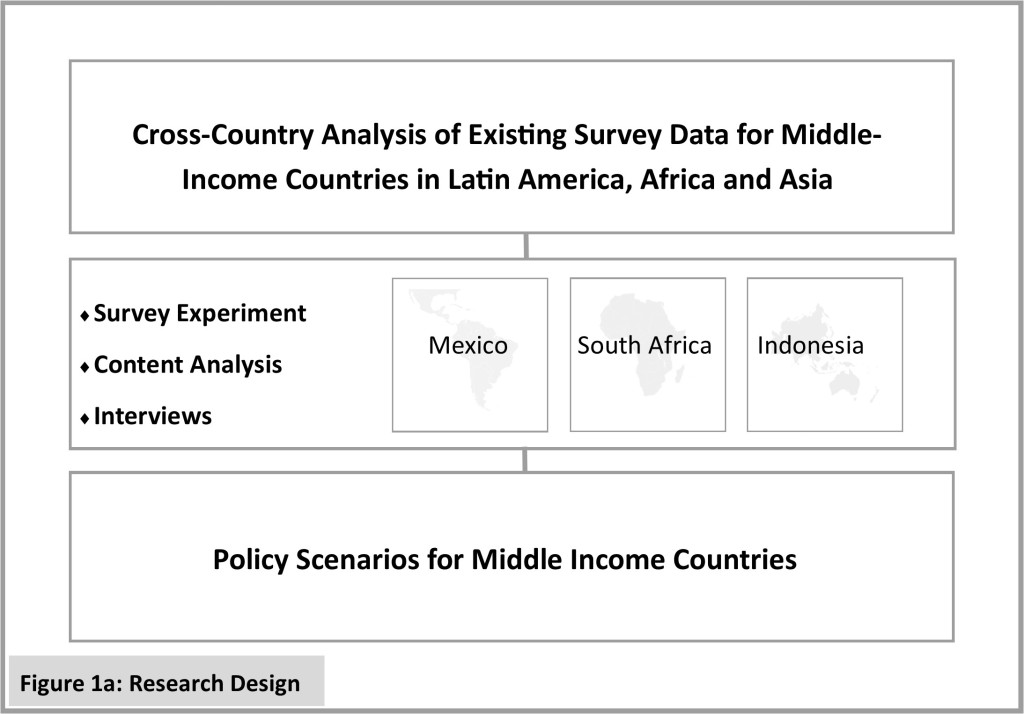

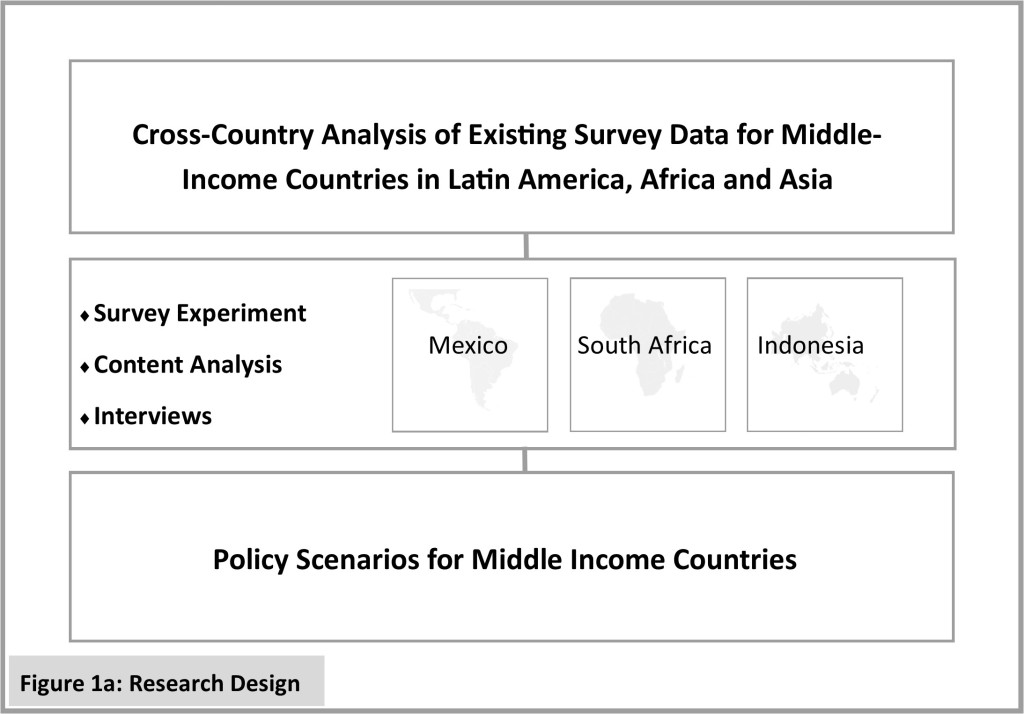

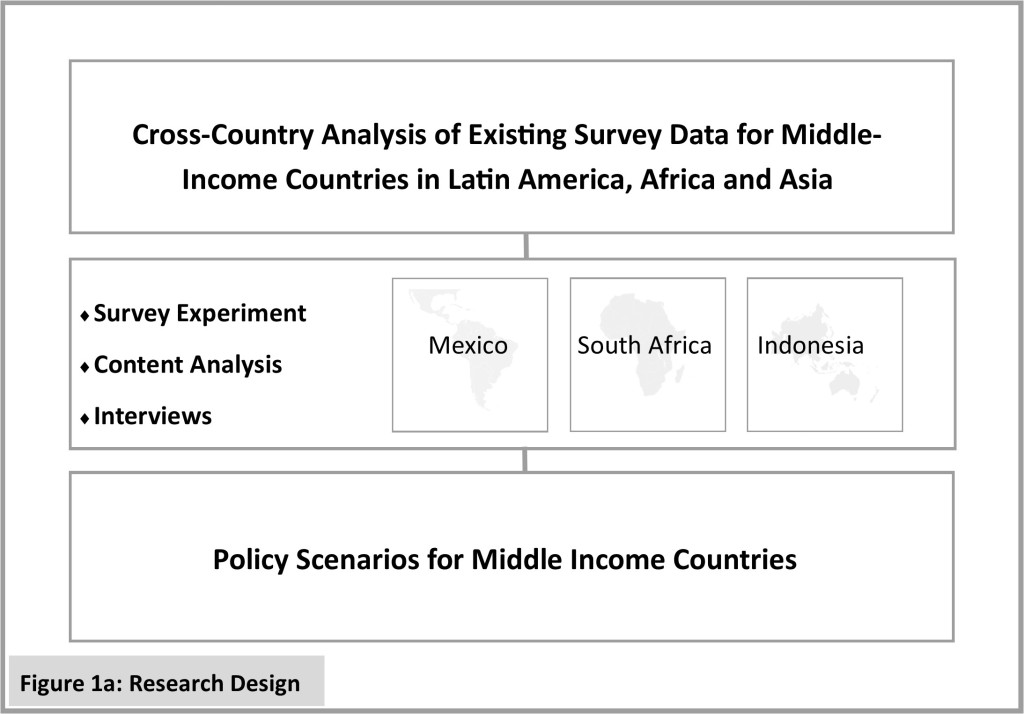

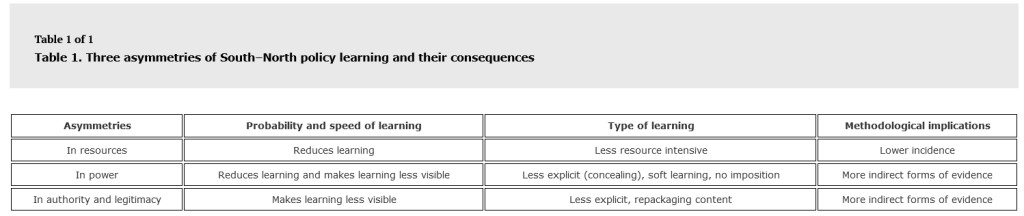

In the introduction to the special issue, I discuss instances of policy learning where the sender comes from the Global South and the recipient is in the Global North. After delineating what we mean by Global South and Global North, I identify some cognitive, methodological and institutional barriers to learning from the Global South. It becomes clear that we underestimate the potential and therefore overlook important innovations. I also discuss three major barriers or asymmetries (see table below) that both account for missed learning opportunities as well as reasons why we do not detect policy learning from South to North. Hence, while we do learn from innovations in the Global South, we do not document and acknowledge this learning adequately.

The special issue consists of four contributions from scholars all across the world, covering cases from Latin America, Africa and Asia. Two of the contributions show examples of glaring missed opportunities. To begin with, Corredor, Grimm, Ceesay and Wondirad document how several African countries dealt with COVID-19 as well as previous pandemics. The Global North often preaches concepts such as One Health, which is an attempt to see health as a holistic problem straddling everything from agriculture, the environment to public health in a narrow sense – but rarely does it do justice. To the contrary, several African countries are at the forefront implementing such holistic, bottom-up approaches to public health. The COVID-19 pandemic is particularly good example how countries in the Global North got stuck in their narrow, top-down logic to dealing with a Global pandemics, while African countries had much more experience built up over time. The authors draw on numerous sources, not the least on their own participant observation working with and in some of those initiatives. While the context for policy learning is very different in countries such as Ethiopia or The Gambia, the abstract principles and the general approach African countries chose gives much stimulus for thought. The authors also point out that the very fact that the administrative capacity is weak creates something one might call a paradox of weak state capacity: it spurs innovation.

Similar learning opportunities for the Global North arise in a completely different field: the way public administrations reach out to emigrant populations. Luicy Pedroza documents the remarkable policy arsenal Latin American countries have crafted to reach out to their emigrant populations, something richer countries could well take a note off. Harnessing an impressive database she and her colleagues compiled (Emigrant Policy Index Dataset – EMIX), she documents the tremendous learning potential how to administer citizens living abroad. Examples are Mexico’s extensive consular service for the diaspora in Mexico, or Ecuador’s representation of emigrants in the national parliament. She also shows that this much more than symbolic politics for many countries in the region, and that rich countries could do worse than studying such practices. For instance countries such as Germany are currently in a sever shortage of ‘skilled workers’. Since they never see themselves as countries of emigration they might lose out on a big pool of potential migrant workers. All in all, Luicy Pedroza not only contributes to the literature on emigrant policies, but also to public administration and public policy in more general.

The other two articles in this special issue take famous policy innovations from the global south and document that they made more inroads into the Global North than commonly acknowledged. Both contributions look at the forms how South-North policy happens, factors that accelerate it, and factors that impede it. It becomes clear that senders in the Global South are often not acknowledged, and that learning often happens in a concealed, repackaged or outright distorted way.

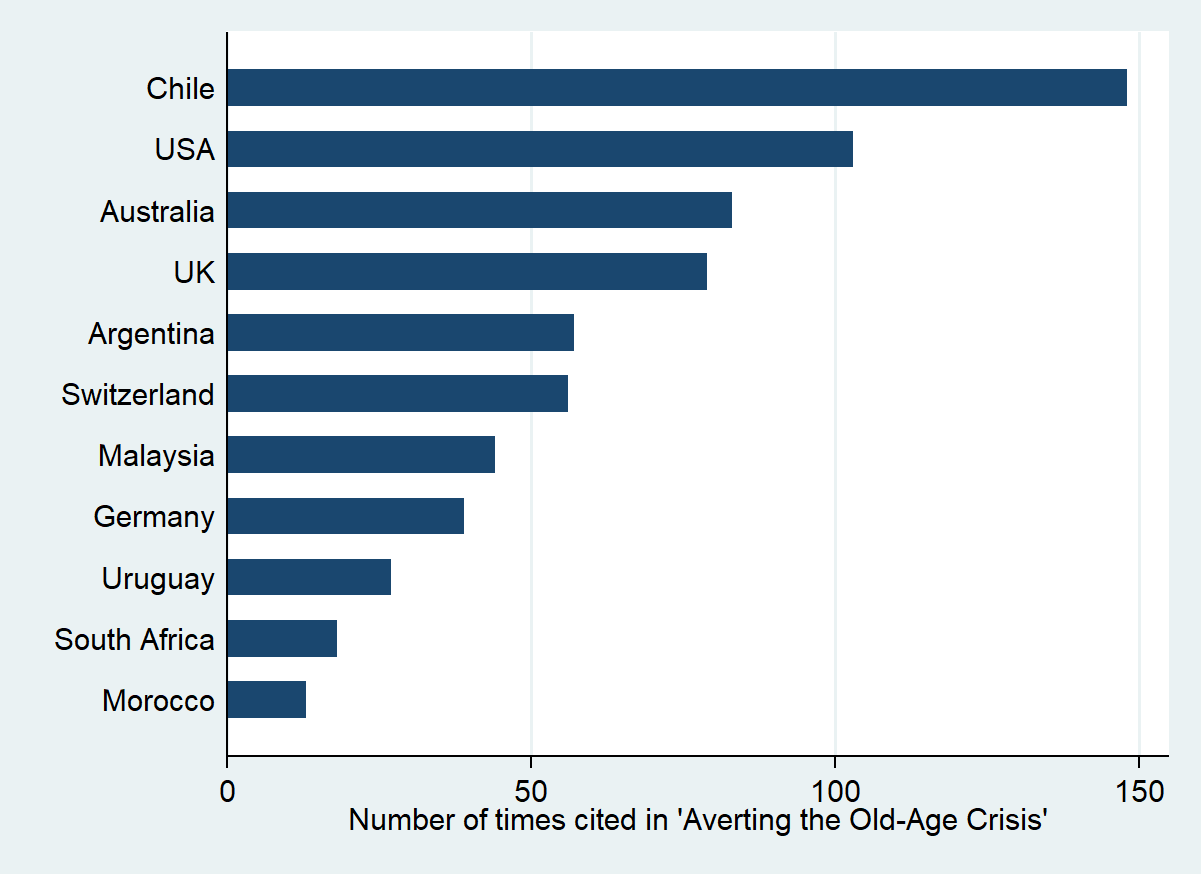

Kemmerling and Makszin, for instance, take the famous and notorious example of the Chilean pension reform (for a deeper discussion see here). While this is a textbook case for policy learning and policy diffusion, the overwhelming part of the narrative deals with the Chilean reform as an inspiration for other countries in the Global South and the former Communist world. The one exception that proves the rule is the US, in which proponents of privatization point at Chile as the testing ground of ideas developed by the famous Chicago school. This phenomenon of policy circulation is well documented. Yet, many governments and international organizations have closely monitored the events in Chile, even if few would dare to admit this. The reason, of course, is that Chile was an international pariah at the time (given the autrocious human rights record of general Pinochet’s military government), which made the way pension privatization happened in Chile totally unacceptable. For this reason in countries like the UK policy learning needed to be repackaged: separating the economic from the political aspects of the reform, and downplaying the importance of the sender, autocratic Chile.

Another example for a famous reform with an underappreciated learning effect in the Global North is the microfinance revolution, and the success of Grameen bank in particular. Again, most scholarly studies would focus on how microfinance inspired by events in Bangladesh spread throughout the Global South. To the contrary, few would systematically document its influence on microfinance institutions and regulations in the Global North. However, there are many clear examples of explicit and implicit learning and outright adoptions as Barua and Khaled demonstrate. The speed and depth of adoptions varied, consistent with the compatibility of the ideational and institutional context in the receiving countries. For instance, the US was much more permissive in this regard than – say – Germany. And yet, policy learning clearly happened from South to North and we should give credit where credit is due.

As a summary, the special issue will be interesting for people studying types and forms of policy learning, transfer and diffusion. It will also be important for those looking at policy innovations around the globe. We also think the special issue contains important lessons for how to level the playing field between research on and from the Global South.