After years of trial and error, we, i.e. Matteo Fumagalli and I, finally got this article out (send me a DM on twitter if you need an ungated version). It is an analysis of the relationship between official development aid of major donor countries and organizations and internal regional inequality in Myanmar. As we are cutoff from the country since last year’s horrenduous military coup, our analysis is mainly for the transition regime 2011-2021, but we think it holds valuable lessons for the country and perhaps also similar cases.

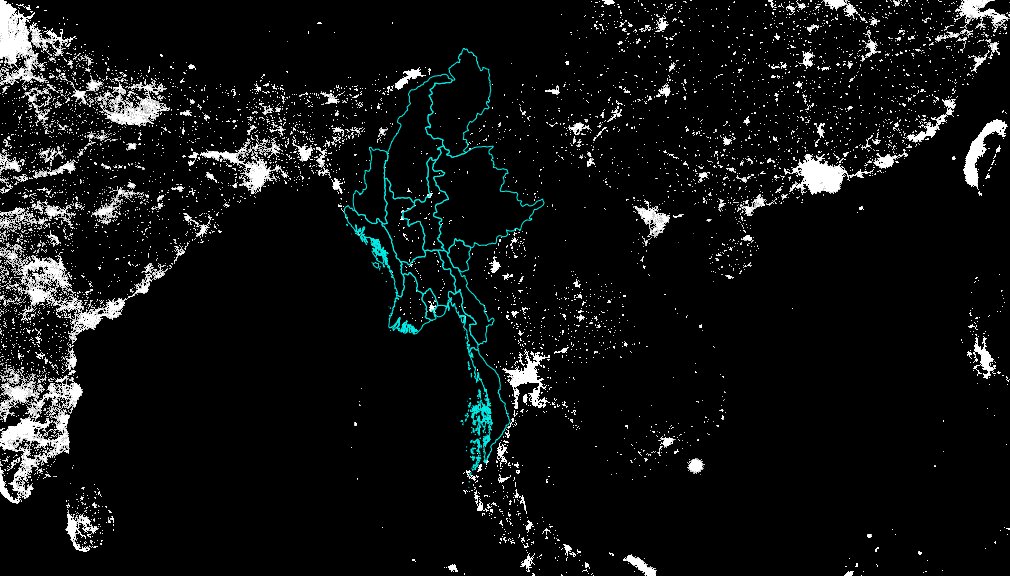

We use several empirical sources: data on night-time luminosity to measure regional inequality between Burmese core regions and the ‘periphery’; DAC data on aid flows to the Myanmar from all donors; interviews with representatives of donors and other key informants; as well as a mini-case study on higher education reform in Myanmar.

We look at donors’ reactions to the explosion of regional inequality in the country. It is noticeable that from 1992 onwards (first available satellite data) and, especially from 2008 onwards with the economic and political opening, there is a tremendous imbalance between economic activity in the Burmese mainland and the rest of the country.

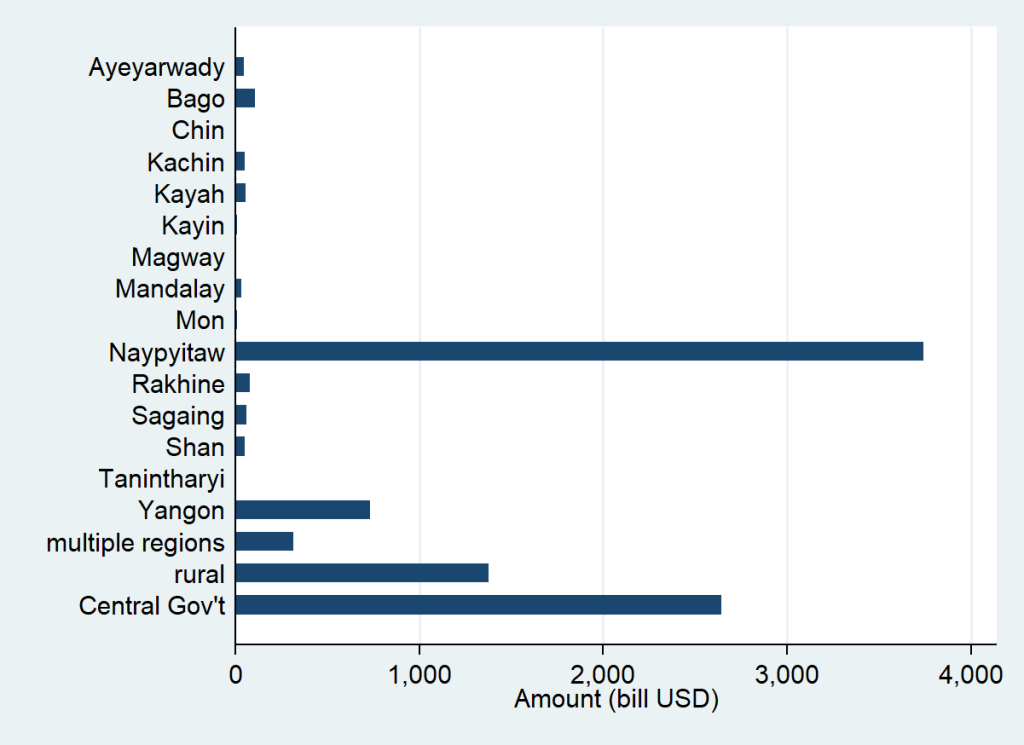

Donors struggled to keep up with this explosion of regional inequality. To a certain degree the share of aid flows that goes to the rest of the country has increased, but it is still dwarfed by flows to the Burmese mainland, and the central government in particular.

We identify several reactions to this problem. Some donors, such as Japan, have chosen the technocratic ‘route’: delivering aid to the rural more isolated regions, but mainly in the form of infrastructure and agricultural projects and not really considering the social and political implications of such aid. Other donors such as the United Kingdom directly address political and social topics, e.g. the Rohingya crisis, but then hit heavy resistance from parts of the hybrid democratic-military regime at the time.

We also draw on our own, naturally somewhat biased and limited experience. We were part of a project of the Open Society Foundation contributing to the reform of the higher education system from 2011 onwards. We realized that it was very hard to deal with a recipient government that was adamant about keeping higher education centralized and focussed on one or two elite universities. If spillover to other regions happened it was mainly indirectly and informally.

While we do not have a ‘magic solution’ for this dilemma it would be good for major donors to acknowledge the enormous problems of regional disparities more directly and also to think about strategies that deal with these problems. For instance, we believe that Germany withdrawing its commitment in Myanmar before the coup, foresake the little bargaining space it had with the hybrid regime before the coup, let alone a way to help remoter, conflict-ridden parts of the country nowadays. See also here for a policy paper written by Matteo.

We are grateful to many people, especially in Myanmar, but also to colleagues who gave us comments. We also acknowledge funding from the British Arts and Humanities Council, the Open Society Foundation, the University of Erfurt and the Thyssen Foundation.

We also learned a lot during the reviewing process. Mixing several different methods and empirical sources made us vulnerable to criticisms from all academic perspectives. While this was painful at times, and considerably delayed the publication of the article, we also acknowledge the problems of Western ‘development experts’ writing on other countries. We hope we stroke a good balance between transparency in our biases and acknowledging our debts.

Dedicated to the brave people in Myanmar.